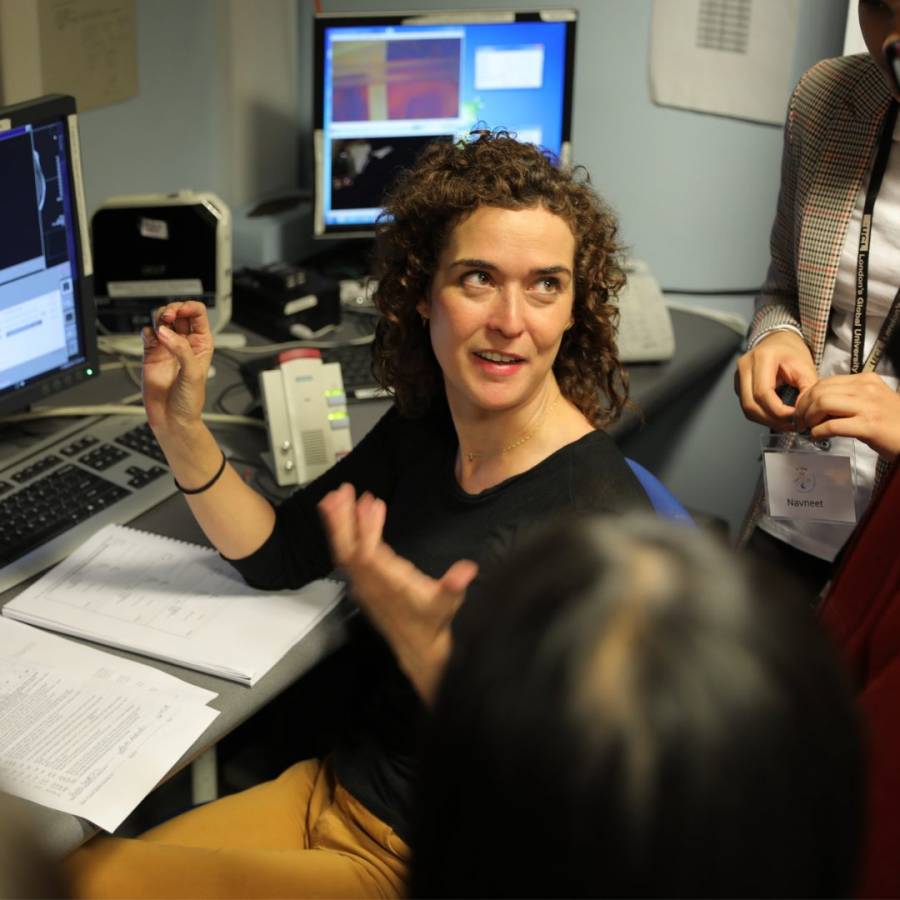

Who is Tessa?

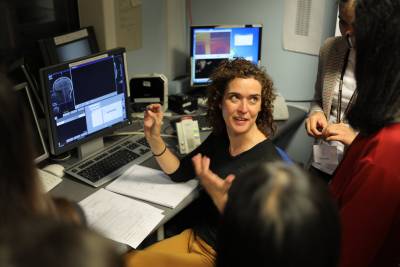

Tessa works as a Neurocognitive Development Scientist, meaning they look at how our brain develops as we grow. Specifically, Tessa heads the Child Vision Lab at the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology.

Tessa’s career began when she began studying Psychology and Medical Biology at the University of Amsterdam. After this, she worked towards a PhD at the Centre for Brain and Cognitive Development at Birkbeck, University of London. The work that Tessa does is interdisciplinary, as the processes behind our vision are so complex. So Tessa must have a complex understanding in multiple areas.

How do our visions of the world change as we age?

Even if you have a perfect vision for your entire life, you will still see the world differently depending on your age. One example of this is the Mooney Test. When you are a child, you might not be able to spot features of an image when it is in high contrast, but as you develop as an adult, you’re able to spot these features much easier.

For example, a child might not be able to spot the nose of the bear in the image below, even after being shown the image in its normal form. But teens and adults might be able to spot it straight away.

So why does this happen? Well, the input being received always stays the same to us, but our memories and experiences change as we grow. There are a lot of other factors impacting how what we see changes over time, and this is what Dr. Tessa is looking at, to ensure that children interact safely with their environment.

What is the future of this work?

Because we understand that the way our brains perceive visions can change over time, this can be used to help treat eye disease in early life. This means we can help restore people’s sight, and understand how our brains react to sight loss.